Our Marketing Team at PopaDex

A Guide to Foreign Asset Reporting Requirements

When you hear acronyms like FBAR and FATCA, it’s easy to feel a bit overwhelmed. But strip away the jargon, and these foreign asset reporting rules are all about one simple concept: financial transparency. The U.S. government just wants a clear map of the financial assets that citizens, residents, and certain businesses hold outside the country.

It’s crucial to think of this as a declaration, not a tax. The whole system was put in place to combat tax evasion and stop people from hiding money offshore. It operates on two main pillars, and the fact that they’re managed by two different government agencies is where a lot of the confusion comes from.

Why Foreign Asset Reporting Is Non-Negotiable

The U.S. government’s approach to foreign asset reporting boils down to two distinct, but sometimes overlapping, filings. Getting them straight is the first step to staying compliant.

The Two Pillars of Reporting

-

FBAR (Report of Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts): This one goes to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), which is part of the Treasury Department. Its main job is to track foreign accounts to flag illegal activities like money laundering. This is a totally separate filing from your annual tax return. The magic number here is an aggregate balance of $10,000 in your foreign accounts at any point during the year.

-

FATCA (Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act): This report is filed with the IRS using Form 8938. FATCA is tied directly to your tax return and ensures you’re correctly reporting any income generated from your foreign assets. The thresholds for FATCA are much higher and depend on your filing status and where you live.

Here’s the key difference: FBAR is about reporting the existence of foreign accounts, while FATCA is about reporting the assets for tax purposes. Depending on your situation, you might need to file one, both, or neither.

A Focus on Transparency, Not Taxation

A common myth is that reporting foreign assets automatically means you’ll pay more in taxes. That’s simply not true. These filings are purely informational. You are taxed on your worldwide income, not necessarily on the assets you hold.

However, failing to report is where the real trouble begins.

The penalties for non-compliance can be brutal, often far exceeding any tax you might have owed. For a non-willful mistake, fines can hit over $10,000 per violation. If the IRS determines the failure was willful, penalties can skyrocket to the greater of $100,000 or 50% of the account balance.

This is why a proactive strategy is the only way to go. For expats especially, these obligations must be a core part of their financial life. Good expat financial planning isn’t just about growing your wealth; it’s about protecting it by ensuring every reporting duty is met. To effectively navigate these complex reporting requirements and ensure adherence, consider leveraging modern tools, such as those found in Top Compliance Management Solutions for Your Business. The goal is to build a seamless system that takes the stress and risk out of the equation.

Defining a Reportable Foreign Asset

Figuring out what actually counts as a “reportable foreign asset” is often the biggest tripwire for U.S. taxpayers. The definition is way broader than just a savings account in another country, and getting this wrong—even accidentally—can lead to serious trouble.

Think of it like cleaning out a storage unit. You can’t just count the big, obvious boxes. To get the full picture, you have to account for the smaller items tucked away in the corners. The IRS and FinCEN take that same all-encompassing view of your financial life abroad.

This means looking past the obvious and considering every financial instrument you have a connection to. Forgetting just one small asset could be enough to push you over the reporting threshold without you even realizing it.

Beyond the Bank Account

One of the most common mistakes people make is assuming that only cash sitting in a foreign bank account triggers these filing rules. In reality, the net is cast much, much wider. Let’s break down the categories you absolutely need to look at.

Common Types of Reportable Foreign Assets:

- Bank Accounts: This is the easy one. It covers your standard checking, savings, and certificate of deposit accounts held at any foreign financial institution.

- Brokerage and Securities Accounts: If you own stocks, bonds, or other securities through a non-U.S. broker, that account is reportable. Owning shares of a Japanese tech company through a brokerage in London is a perfect example.

- Mutual Funds and Similar Investments: Any stake in a foreign-domiciled mutual fund, hedge fund, or private equity fund has to be factored into your total.

- Retirement and Pension Plans: Foreign accounts that function like a 401(k) or IRA are almost always reportable.

- Insurance Policies with Cash Value: A life insurance or annuity contract from a foreign insurer is considered a financial asset if it has a cash surrender value you can access.

This isn’t a complete list, but it hits the big ones that filers frequently miss. The key question to ask is whether the asset is held with a foreign financial institution.

What About Business and Other Interests?

The rules don’t stop at personal investments. They extend deep into business ownership and other indirect financial interests, which is where things can get particularly tricky because ownership isn’t always straightforward.

For instance, an interest in a foreign entity like a corporation, partnership, or trust is generally reportable. If you own a 10% stake in a family manufacturing business in Italy, that partnership interest counts as a specified foreign financial asset for FATCA. When you get into these more complex ownership structures, it’s worth exploring different strategies for offshore company setup, as they often involve the very entities that trigger these reporting rules.

The core principle here is “financial interest or signature authority.” This is critical. Even if an account isn’t technically in your name, if you have the power to control its funds—say, as a signatory on your parent’s account or a company account—you may have a reporting obligation.

This broad definition is designed to create total transparency and stop people from using complex legal structures to hide assets. It’s a crucial distinction that catches a lot of people by surprise. You have to carefully assess not just what you own, but also what you control. Given the severe penalties for getting it wrong, a detailed, honest inventory of every foreign financial tie is the only safe way forward.

Understanding the Reporting Thresholds

One of the trickiest parts of foreign asset reporting is figuring out if you even need to file in the first place. A reporting obligation only kicks in if the value of your assets crosses a specific financial line. These triggers are where many people get tripped up, either by underestimating what their assets are worth or by misunderstanding which rules apply to their situation.

Think of these thresholds as tripwires. If your financial footprint abroad is small enough, you can walk right past them without a problem. But the moment the total value of your assets hits a certain number, you’ve triggered a reporting requirement you can’t ignore. The two big ones, FBAR and FATCA, have completely different tripwires, and knowing the numbers is step one.

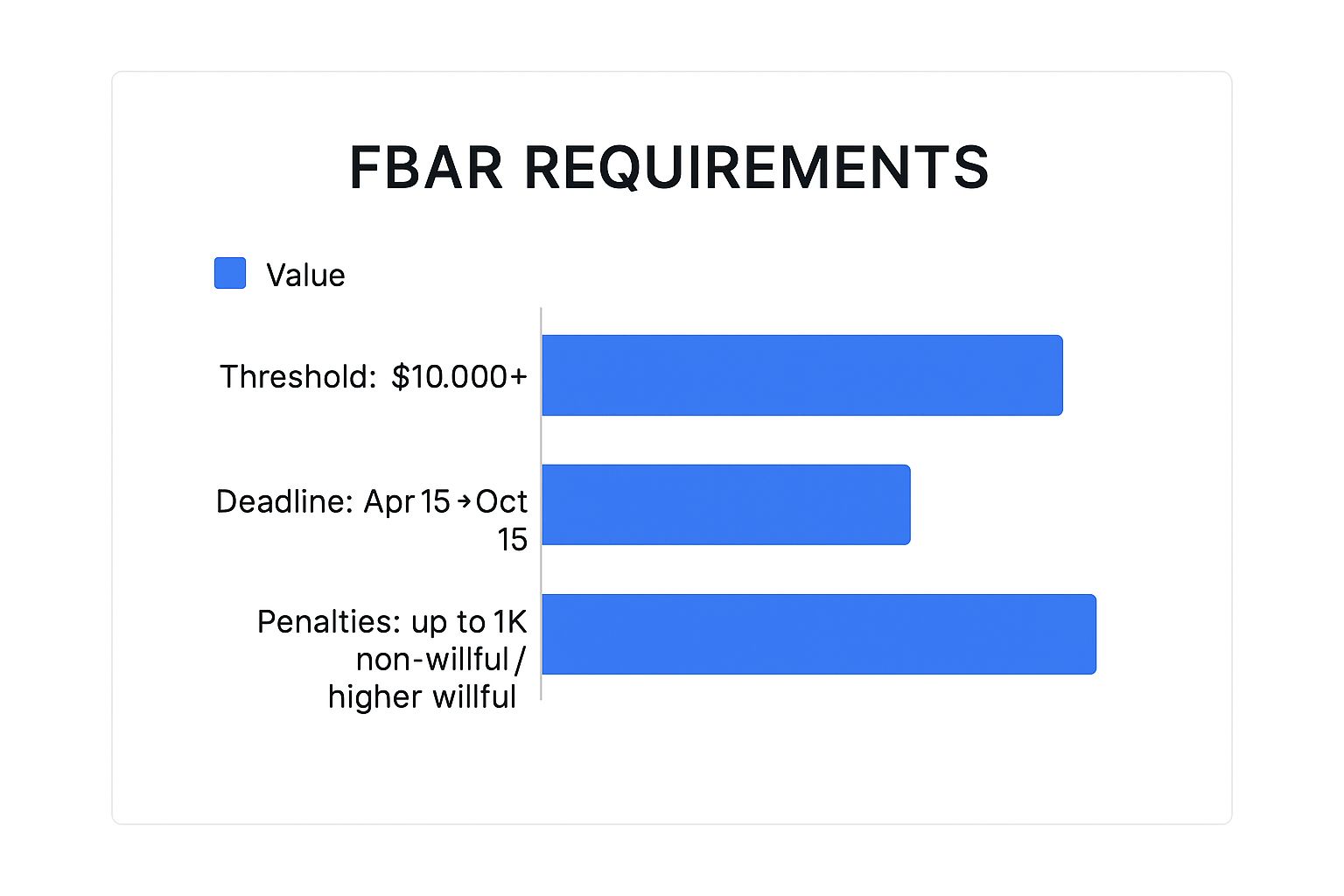

The infographic below gives you a quick snapshot of the FBAR filing and its famous threshold.

This visual is a great reminder of FBAR’s surprisingly low $10,000 trigger—a number that catches a lot of people off guard.

The FBAR Aggregate Value Threshold

The FBAR requirement, which you handle using FinCEN Form 114, has a straightforward but often misunderstood threshold. You must file an FBAR if the aggregate value of all your foreign financial accounts went over $10,000 at any point during the calendar year.

That word “aggregate” is the key. This isn’t about a single account hitting $10,000. It’s about the combined peak balance of all your foreign accounts.

Let’s break it down with an example. Say you have three accounts:

- Account A in France with a high-water mark of $4,000

- Account B in the UK that peaked at $5,000

- Account C in Japan that hit $2,000

On their own, none of these accounts cross the line. But add them up—$11,000—and you’ve got an FBAR filing obligation for all three. The government designed it this way to stop people from just spreading their money across smaller accounts to fly under the radar.

The More Complex FATCA Thresholds

While the FBAR has one number for everyone, FATCA reporting (on Form 8938) is a bit more complicated. The thresholds are much higher, but they change based on your tax filing status and whether you live in the U.S. or abroad. This makes sense, as FATCA is tied directly to your tax return, and the IRS is more focused on those with substantial offshore assets.

Since the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) was introduced in 2010, the rules have gotten a lot tighter. A single taxpayer living in the U.S. has to report if their foreign assets are worth more than $50,000 on the last day of the tax year or topped $75,000 at any point during the year. For married couples and folks living abroad, those numbers are even higher. You can dive into the specifics of FATCA reporting from the IRS for more detail.

Key Takeaway: You could easily be required to file an FBAR but not a FATCA return. On the flip side, it’s almost impossible to have a FATCA obligation without also needing to file an FBAR, simply because the FBAR threshold is so much lower.

This difference is a huge deal for smart cross-border financial planning. If you’re trying to manage your assets to stay below these lines, you have to know both sets of rules inside and out.

To make these different requirements easier to digest, the table below puts them side-by-side.

FBAR vs FATCA Reporting Thresholds at a Glance

This table gives you a clear comparison of the minimum asset values that trigger FBAR and FATCA reporting based on your personal situation.

| Filing Status / Location | FBAR (FinCEN 114) Threshold | FATCA (Form 8938) Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| All Filers (Any Location) | Aggregate value over $10,000 at any time. | N/A |

| Unmarried (Living in U.S.) | Same as above. | Over $50,000 on the last day of the year OR over $75,000 at any time during the year. |

| Married Filing Jointly (in U.S.) | Same as above. | Over $100,000 on the last day of the year OR over $150,000 at any time during the year. |

| Unmarried (Living Abroad) | Same as above. | Over $200,000 on the last day of the year OR over $300,000 at any time during the year. |

| Married Filing Jointly (Abroad) | Same as above. | Over $400,000 on the last day of the year OR over $600,000 at any time during the year. |

This breakdown lets you pinpoint the exact numbers that apply to you, taking the guesswork out of the equation and helping you figure out your filing duties with confidence.

How to Navigate FBAR and FATCA Filings

Alright, so you’ve figured out you need to file. This is where the rubber meets the road, and honestly, where a lot of people start to sweat. But don’t worry. Once you get a handle on the two main forms—FinCEN Form 114 for FBAR and IRS Form 8938 for FATCA—the whole process becomes much clearer.

They might look similar on the surface, but they’re completely different animals. Think of your FBAR as a report for the Treasury’s financial crime unit (FinCEN), while Form 8938 is an extra page you staple to your annual tax return for the IRS. They report to different agencies, serve different purposes, and have their own unique set of rules. Getting the details right on both is non-negotiable.

Mastering the FBAR: FinCEN Form 114

First up, the FBAR. This one is filed electronically through FinCEN’s BSA E-Filing System. I can’t stress this enough: you do not mail this form with your taxes. It’s a totally separate filing.

To fill it out, you’ll need to roll up your sleeves and gather some specific details for every single foreign account. A simple summary won’t cut it.

What You’ll Need for Your FBAR Filing:

- Account Holder Info: Your full name, address, and taxpayer ID number.

- Bank Details: The name and mailing address of the foreign financial institution.

- Account Number: The specific number or identifier for your account.

- Maximum Account Value: The highest balance the account hit during the calendar year, converted to U.S. dollars.

That last point—the maximum value—trips a lot of people up. You have to find the peak balance for each account during the year, then use the Treasury Department’s official year-end exchange rate to do the conversion. It takes a little digging.

A critical piece of the FBAR puzzle is understanding “signature authority.” It’s not just about ownership. If you have control over the funds in an account—even if it belongs to your boss or a relative—you probably have to report it. Overlooking this broad definition is a classic, and often costly, mistake.

Tackling FATCA: IRS Form 8938

Now for Form 8938, the Statement of Specified Foreign Financial Assets. Unlike the FBAR, this form is a direct part of your annual U.S. income tax return (like the Form 1040). If your assets cross the FATCA threshold, you absolutely must include this form when you file with the IRS.

The information you need for Form 8938 has some overlap with the FBAR, but there are important distinctions. For example, FATCA wants to know both the maximum value and the value on the last day of the tax year.

Essential Details for Form 8938:

- Asset Type: You need to clearly state what the asset is—a bank account, stocks, a partnership interest, etc.

- Maximum and Year-End Value: Report both the peak value during the year and the value on December 31st, converted to USD.

- Income Details: This is a big one. The form requires you to list any income the asset generated (like interest or dividends) and point to exactly where you reported that income on your tax return.

That final requirement gets to the heart of what FATCA is all about: connecting your foreign assets directly to your taxable income. The IRS wants to see that you’re properly reporting every dollar earned from your offshore holdings. It’s a level of detail that’s crucial for managing your finances, especially with a global portfolio. For more tips on handling money across borders, check out our guide to expat banking.

Ultimately, getting these filings right comes down to methodical preparation. Gather your statements, pinpoint those peak values, and treat each form as its own unique task. A structured approach is your best defense—it ensures accuracy and brings some much-needed peace of mind to a notoriously complex corner of finance.

The Real Penalties for Non-Compliance

Let’s be blunt: failing to report your foreign assets isn’t a mistake the government just shrugs off. Ignoring these filing requirements can unleash financial penalties so severe they can completely wipe out any tax savings you might have been hoping for. The rules are designed to be punitive, driving home the point that financial transparency isn’t optional.

It’s absolutely critical to understand the difference between a simple mistake and deliberate evasion, because the IRS sees these two scenarios in a completely different light. That distinction is what separates a stiff fine from a life-altering financial blow.

The Cost of an Honest Mistake

Even if you genuinely didn’t know you had to file, the penalties for a non-willful violation can still sting. This category is for situations where you were truly unaware of your filing obligation or just made an accidental error on the forms.

For these kinds of non-willful oversights, the IRS can hit you with a penalty of over $10,000 per violation. Think about that for a second. If you unknowingly missed reporting two separate foreign accounts, you could be looking at two separate penalties. You can see how quickly the cost of a simple error can stack up.

When Negligence Becomes Willful

The financial landscape changes dramatically if the IRS decides your failure to file was willful. This means you knew you had a reporting duty but chose to ignore it, acted with reckless disregard for the rules, or were “willfully blind” to your obligations. The penalties here are designed to be devastating.

For willful non-compliance, the fines get serious, fast.

- The IRS can impose an automatic $10,000 penalty for each failure to file forms like the FBAR or FATCA documentation.

- If you don’t fix the issue within 90 days of an IRS notice, they can add another $10,000 penalty for each 30-day period that passes, up to a maximum of $50,000.

- Even more frightening, willful FBAR penalties can skyrocket to the greater of $100,000 or 50% of the balance in the unreported account.

- In the most extreme cases, criminal charges could mean fines up to $250,000 and five years in prison.

You can find more expert analysis on these penalties and how to deal with them by reading about navigating global asset compliance.

A Real-World Scenario: Picture a taxpayer who knowingly decided not to report a foreign account holding $250,000. Under the willful penalty rules, they aren’t just facing a fine—they could be penalized 50% of the account’s value. That’s a staggering $125,000 penalty, which could be applied for each year of non-compliance.

This one example makes the enormous financial risk crystal clear. The potential penalties can easily erase a huge chunk of the very assets you failed to report. With consequences this severe, proactive and honest compliance isn’t just the best strategy—it’s the only one. The risk of staying silent is far, far greater than the effort it takes to file correctly.

The Global Shift Towards Financial Transparency

The strict foreign asset reporting rules in the U.S. aren’t happening in a vacuum. They’re a huge piece of a coordinated global movement to tear down the old walls of bank secrecy and drag offshore accounts into the light. For decades, stashing assets overseas was a go-to strategy for some, but that era is officially over.

Think of it this way: in the past, each country’s financial system was like a private island with murky, unguarded shores. Today, those islands are all connected by a massive network of data-sharing bridges, built to make sure everyone pays their fair share. This web of connections means information now flows freely—and automatically—between tax authorities all over the world.

This new reality fundamentally changes the game for U.S. taxpayers with assets abroad. The whole idea of a “hidden” account is now a dangerous fantasy.

The Rise of Automatic Information Exchange

The engine driving this whole transformation is a framework known as the Common Reporting Standard (CRS). It’s the plumbing that makes the Automatic Exchange of Information (AEOI) possible between countries. While the U.S. has its own system with FATCA, CRS is the global equivalent, with over 100 countries participating.

Here’s a simple breakdown of how it works in the real world:

- A U.S. citizen opens a bank account in Germany (a participating country).

- The German bank immediately flags the account holder as a U.S. person.

- That bank then reports the account information to Germany’s tax authorities.

- Through international agreements, Germany automatically zaps that data straight to the IRS.

This isn’t a one-off thing. It happens systematically, without the IRS ever having to ask. It’s a proactive dragnet designed to catch anyone not playing by the rules.

The OECD’s Automatic Exchange of Information standard requires participating countries to share mountains of financial data every year. By 2022, this system was swapping information on roughly 123 million bank accounts worldwide, representing about €12 trillion in assets. You can dig into more of these insights on tax transparency directly on the OECD’s official page.

This global cooperation creates one critical reality for taxpayers: in today’s financial world, there’s effectively nowhere left to hide. Your foreign bank is no longer a silent partner; it’s a reporting agent for its government, which in turn reports directly to the IRS.

Why Voluntary Reporting Is Essential

This worldwide shift makes coming forward voluntarily more critical than ever. The IRS isn’t just taking your word for it anymore; it’s getting a firehose of data directly from foreign banks, giving them powerful tools to cross-reference your tax return and spot discrepancies.

Trying to conceal foreign assets is simply no longer a viable strategy. It’s a matter of when, not if, unreported accounts will be discovered. Understanding this international context highlights why meeting your foreign asset reporting requirements is the only sound path forward.

Proactive disclosure isn’t just about following the rules—it’s about protecting yourself in a world of unprecedented financial transparency.

Common Questions on Foreign Asset Reporting

Even after you’ve got the basics down, real-life situations can throw some tricky curveballs into your foreign asset reporting. Let’s walk through some of the most common points of confusion to give you more confidence as you get your filings in order.

How Do I Handle Jointly Owned Accounts?

This one comes up all the time, especially for married couples or families with shared accounts overseas. The rule is actually pretty straightforward: if you’re a U.S. person with a financial interest in or signature authority over a joint account, you have a reporting duty.

Each U.S. person on that account needs to file their own separate FBAR. And here’s the critical part: you must report the full value of the account, not just your share. For example, if you and your spouse have a joint foreign account that hit a high of $50,000 during the year, you both have to file an FBAR, and you both report the entire $50,000 peak value.

What if I’ve Never Filed Before?

Realizing you’ve missed past deadlines can be a gut-wrenching moment, but the absolute worst thing you can do is ignore the problem. The IRS has several programs designed to help people get back on track, and coming forward voluntarily is always your best move.

The most common path is the Streamlined Filing Compliance Procedures. This program is built for taxpayers whose failure to file was non-willful—basically, you made an honest mistake or just didn’t know you had to. It lets you catch up on old tax returns and FBARs with a much friendlier penalty structure.

It is absolutely critical to sort this out before the IRS finds you. Once they open an investigation, your chances for voluntary disclosure and reduced penalties often vanish. Proactivity is everything here.

How Do Currency Fluctuations Affect Thresholds?

This is a huge trip-up for many filers. To figure out if you meet the reporting thresholds, you have to convert all your foreign currency balances into U.S. dollars. It’s a non-negotiable step where mistakes can easily happen.

For both FBAR and FATCA, you can’t just pick a rate you like. You must use the official U.S. Treasury Department’s Financial Management Service year-end exchange rate for that specific tax year.

- For the $10,000 FBAR threshold: You need to identify the highest value each account reached in its local currency during the year. Then, convert that peak value to USD using the official year-end rate, and finally, add all those peak values together.

- For Form 8938: The process is similar for calculating both the maximum and year-end values of your assets.

This means a big swing in exchange rates could easily push you over the reporting limit one year, even if your account balance in euros or yen never changed. Careful, methodical conversion is the only way to get it right.

Ready to get a clear, consolidated view of all your assets, both foreign and domestic? With support for over 15,000 banks across 30+ countries, PopaDex makes it simple to track your complete financial portfolio in one place. Take control of your net worth and make informed decisions with confidence. Start for free on PopaDex today.